DSP-17 #1.1: Modern computing for musophobes

Note:

Some of the things that I want to publish here (like this article) aren’t gonna be exactly about my Linux course. For that reason, I’ll assign to them numbers like 1.1, 2.3 etc., depending on which course-related post comes before.

Are you a touch typist? You probably are, and I am one too. Do you like moving your hand away to reach for the mouse in order to do that one little shit-of-a-thing that can’t be dealt with using a shortcut? Of course you do… not!

This time, I’d like to share some insight on ways to eradicate the wretched rodent from your workflow and minimize the distraction involved. Because of the scope of this series, the solutions I’m about to present are meant mainly for the Linux user, being mostly compatible with macOS and other *nix flavors. Let’s zoom in on the things that could help you better cherish the safety of your home row.

Before we abandon the mouse completely

Pointing devices do bring some strong arguments to the table. They assume an undeniable position in tasks like creating digital art or CAD. Things like going through an application for the first time can also prove your mouse worthy - e.g. you don’t have to wonder which key does what, you just find the option in a menu and often learn the shortcut in the process.

Stop worrying and love the shell

I’ve gotta admit, my terminal-fu grew in my skill set to become the keystone of my process as a programmer. I love text interfaces, for they are as concise and expressive as it gets.

Before we advanced into graphical user interfaces, there was next to no other option than to rely on the keyboard alone. Mice would only save you a couple keystrokes when moving around in your editor (which, confronted with a text UI masterpiece like vim wouldn’t necessarily mean an improvement). Even today almost every text application is easy on the mouse, if supporting it at all. For that reason alone, it may be worth your while to give the ancient way a shot, but the benefits don’t end there:

-

Consistence across distributions - thanks to common UNIX specifications

like POSIX, many *nix OSes share the well known command-line

utilities like

sed,grep,tarorvi, regardless of the system in question being Linux, BSD, macOS or whatever - Almost everything you do in a terminal is scriptable - shells, pipes, exit codes, stdin/stdout redirections - these make for very powerful building blocks for scripts that can repeat almost anything you do in a terminal session

- Decent performance on potato-grade machines - it’s not much of a surprise that drawing elements from a finite set of predefined font characters is way cheaper than displaying sophisticated GUIs on the user’s screen, let alone supporting the underlying desktop environment. Often even the dumbest of chips know how to speak over a serial console. Armed with the bunch of text-based tools, we can do great things using machines of not-so-great performance

- Everything works over SSH - a traditional SSH shell works way faster than most graphical remote desktop solutions, is really good at handling twitchy network connections, requires a mere fraction of the bandwidth and is a secure, versatile industry standard that supports all terminal programs by design (hence the name Secure SHell)

-

Where there is a shell, there is always a way - things break, and when

they do, you can often find yourself left with an ascetic handful of tools in

a terminal flashing at you cheerfully. After becoming proficient with your

system’s core utilities, you should be able to diagnose your problem to some

extent. Hell, in a “broken X11” kind of situation, you could simply fire up a

text-based web browser (like

lynxorw3m), find the solution and apply it right away! But the possibilities certainly don’t end at X11’s whims. -

You’re gonna look like a hacker - no explanation needed,

CLI is the

!

!

Vim - the editor

You may have already guessed that I really, really like vim. Vi

Improved (or vim for short) is a text editor created by Bram Moolenaar in 1991.

Vim is in fact a modern take on vi, the ancient editor found in UNIX, written

by Bill Joy in 1976 (only 4 years after Dennis Ritchie designed C!). Vi-style

key bindings seem to transcend all space and time, as there even exist key maps

for vi[m]’s infamous archenemy - emacs.

Why use it?

Vi’s renowned interface works by providing the user with several modes that segregate different actions performed on a file - the editor gives your keys different meanings depending on the mode you’re in. This design allows for maximizing shortcut ergonomy, preferring single keystrokes over painstaking combinations, and keeping you in the alphanumerical block as long as possible - pretty much what we’re going for, aye?

But how long do I need to stay in my mom’s basement to learn this… thing?

The most straightforward way of learning vim is to fire up vimtutor - the

simple tutorial bundled with the editor’s package. Vim has one steep learning

curve, which often becomes the subject of jokes - most notably about exiting the

editor, which doesn’t work with the usual Ctrl+C shortcut (vimtutor tells you

about exiting vim in Lesson 1.2 ![]() ). Vim is difficult to

learn, but your effort will pay off. Its interface is very efficient and in fact

functions like a sort of language for text editing, widely used even outside

the editor, e.g. a bunch of keystrokes like

). Vim is difficult to

learn, but your effort will pay off. Its interface is very efficient and in fact

functions like a sort of language for text editing, widely used even outside

the editor, e.g. a bunch of keystrokes like d10w would translate to “delete

10 words”, which would do roughly what it says, deleting the next ten words

after cursor.

Enough about vim, if you’re not buying into my shameless propaganda, that’s perfectly fine. There’s always emacs and other great text editing solutions to try.

A word on terminal multiplexing

Having split-screen terminals is awesome, but do you know what’s even better?

That’s right, it’s letting a terminal program do the splitting. Using a

terminal multiplexer in fact enables you to have multi-terminal sessions over a

single SSH (or serial) connection! The most prominent terminal multiplexers (in

descending order by popularity) consist of screen, tmux, and byobu. I’m

the most comfortable with tmux, which is found in more systems than byobu and

still has more functionality than screen.

Don’t leave the Web out!

One day, I was lucky to find out that one can successfully browse the web without a mouse. The market-leading browsers offer some very nifty solutions to achieve that. (Almost) needless to say, vi’s omnipresence strikes again, as most mouseless browser plugins base on vi-like bindings, which will certainly benefit those who already know vim.

If you’re a Firefox user, I can recommend you VimFx - a very well integrated

extension with a minimal, non-invasive set of features. Even if the website

you’re viewing has its own keyboard shortcuts, you can always disable the plugin

completely with a single i keystroke or by just choosing an appropriate option

in the plugin’s menu. If you forget a key in VimFx, you can always open the

cheat-sheet dialog by pressing ? in “normal” mode.

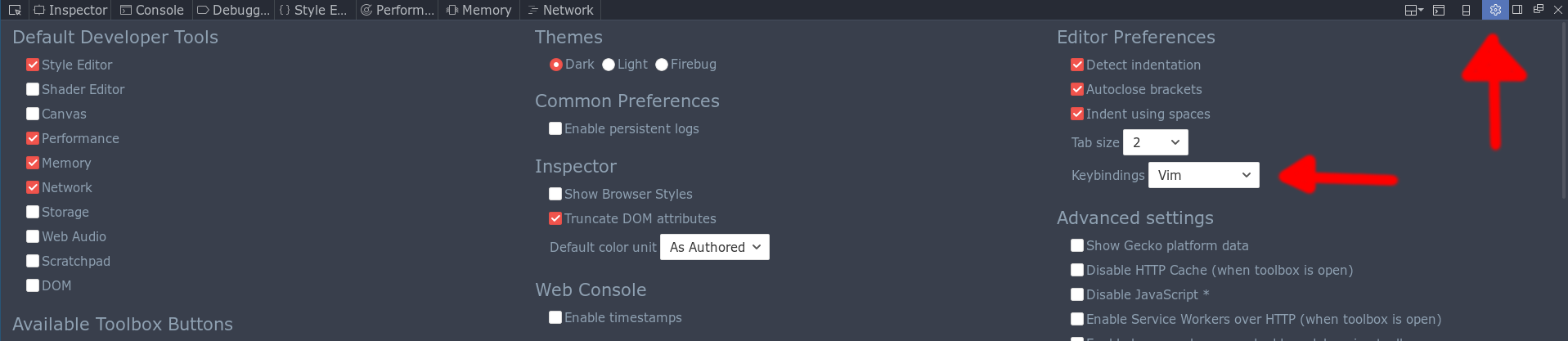

From a web developer’s standpoint, it may be worth noting that Firefox has a vim mode in its development tools:

Just hit F12 and have some fun!

Pave your screen with tiling windows

Finally, the last thing which I’d like to cover - desktop environments. A great

use for your keyboard in that department is offered by the tiling window

manager desktop environment family. The “tiling” part simply means that every

window tries to take as much space as possible while sticking to a predefined

method of placing new windows. The most popular examples involve environments

like i3, awesome, xmonad or dwm.

Personally, I fell in love with i3, as it offered me the most approachable defaults and an easy to grasp configuration file + it integrates with multiple monitors easily. Also, it knows about special cases where tiling should be turned off and supports mixed floating and tiling modes.

i3 in action on a dual-head setup

If you think about it, most of the tools which I’ve described allow for different kinds of tiling, be it vim splits, tmux splits or i3 windows. This makes for quite some liberty to choose the best window layout for a given task.

Conclusion

With the above, I hope I managed to show you a fun new way to interact with your machine. If you have anything to say or a question to ask, feel free to leave a comment below.

![]()

![]()

![]()